Enrollment is down compared to August of last year.

There was a shortfall between the actual number of students and the projected number of students that were originally projected for fall 2011, according to Rebecca Vazquez-Skillings, vice president for Business Affairs.

The shortage is somewhere in the range of 60 students, Vazquez-Skillings confirmed.

“There’s sufficient to be concerned about,” she said.

She said a shortage of 27 traditional undergraduate students was factored into budget planning for 2012 as a cushion.

“That would then provide us with some level of buffer, so if we lost those 27 students, we hadn’t planned programs, activities, etc. based on a budget that we weren’t going to meet,” Vazquez-Skillings said.

The next University Summit on Oct. 3 will discuss what the current enrollment shortfall means for the 2012 budget, including whether cuts will need to be made. Vazquez-Skillings said she hopes that budget cuts won’t even be a part of the discussion.

“Maybe we are talking about some level of reallocations to certain priorities. That’s what I’m hoping for,” she said.

If cuts do enter the picture, Vazquez-Skillings said her goal is to make sure that changes will be invisible to students.

“My goal is that the student experience will look no different to you. That’s my goal,” she said.

When comparing revenue to enrollment, she said it’s important to focus on the number of part-time students because those students pay by the credit hour.

The number of credit hours directly affects revenue more than the number of full-time undergraduates enrolled.

“That’ll help me get a better sense of what the revenue is really going to look like,” she said.

Graduate students and students who go over the credit hour limit of 18 hours are also charged on the basis of credit hours produced, Vazquez-Skillings said. This is crucial for determining revenue.

“You might have more revenue with less students,” she said.

Otterbein is down 50 part-time undergraduate students and five graduate students from fall 2010, according to the fall quarter 2011 census enrollment report, a compilation of detailed undergraduate and graduate enrollment statistics.

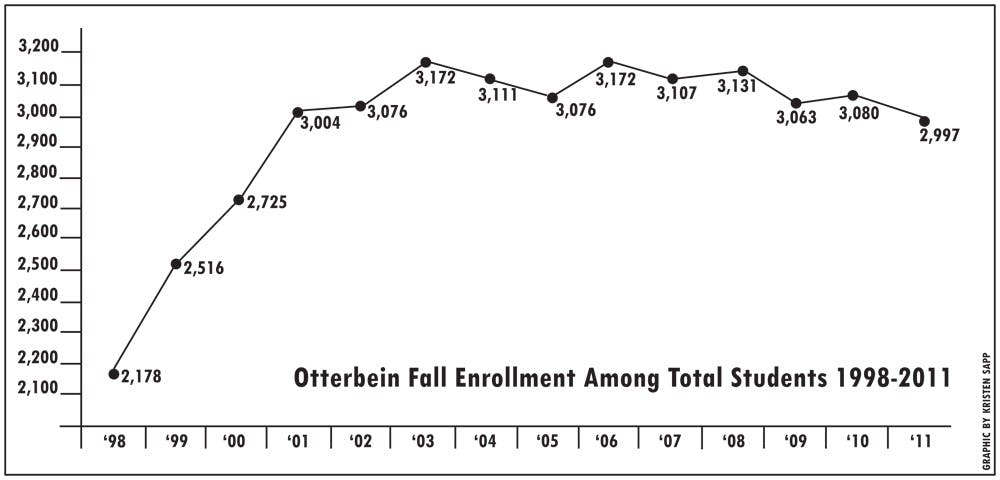

In general, the university has gone down from 3,080 total students to 2,997 total students.

Last February, during the quarterly budget summit (now called the University Summit), enrollment was identified by Vazquez-Skillings as Otterbein’s key revenue driver.

Vazquez-Skillings doesn’t think that a shortfall in enrollment is uncommon among universities due to Ohio’s declining high school graduation rate and the poor economic conditions.

She said it’s important to address why students aren’t staying at Otterbein before completely blaming the economic climate, because the real reason may be pushed aside.

The school has been placing a lot of attention on retention, so it needs to get a better understanding of why students aren’t staying, she said.

“Of course it’s dismaying when you see that we’re still not retaining at the level, but it’s not because of a lack of effort,” she said. “We just need to keep working on it.”

Last year’s news of higher retention rates plays into the university’s continued efforts to maintain and increase retention.

At last February’s summit, retention efforts were identified by Amy Jessen-Marshall, former associate vice president of Academic Affairs.

The MAP-Works survey was implemented to gauge students in danger of withdrawal, those in little danger of leaving and those in the middle. Retention efforts

were focused on those in the middle, according to Jessen-Marshall.

This year, a new platform called Hobson’s Retained is being implemented. It will act as an early alert system, raising a red flag to provide intervention to a student who might leave, Vazquez-Skillings said.