Once readily available, public records dealing with safety issues have become sparse since Otterbein University commissioned its own police department.

Since September 2011, the Tan & Cardinal and Otterbein360.com have requested records including campus crime reports, personnel files and the Police Department budget.

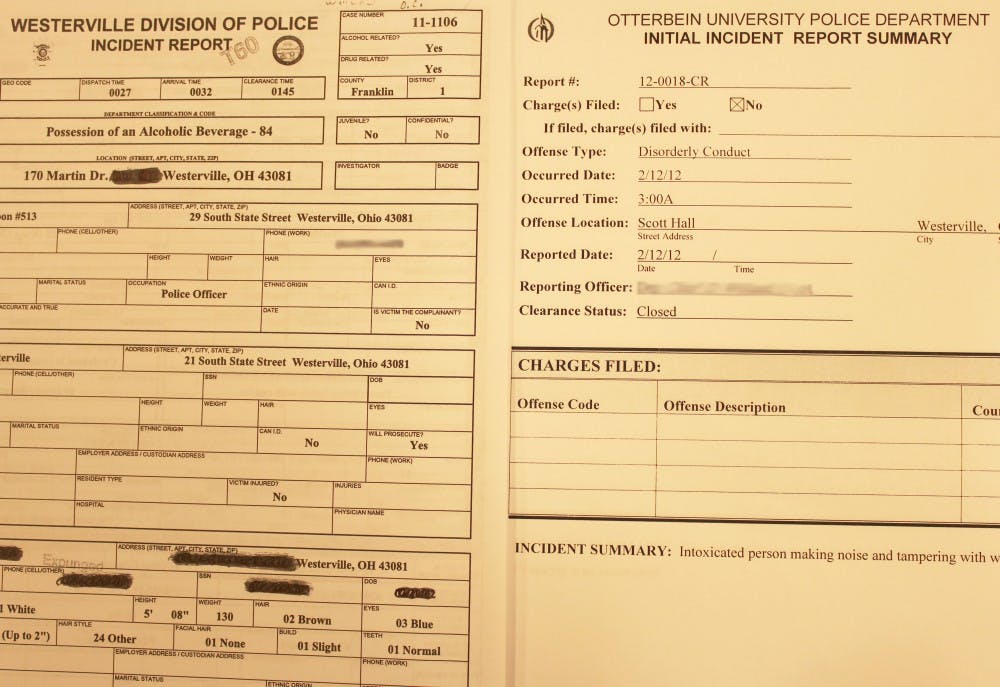

Although the Police Department budget total was later disclosed, personnel files were not released and campus crime reports were scant.

The Otterbein Police Department said that because Otterbein is a private institution, it does not need to comply with the Ohio Public Records Act and does not have to release full documentation.

Access to Otterbein police records

The Ohio Public Records Act states public offices are required to make available public documents for copying and investigation purposes.

A public office is defined by the Ohio Public Records Act as “any state agency, public institution, political subdivision or other organized body … established by the laws of the state for the exercise of any function of government.”

Otterbein is a private institution. According to the Ohio Public Records Act, a private entity can be defined as a public office if it performs a governmental function.

Stephen Dyer, a former state representative and a lawyer in the Akron area, said the Otterbein Police Department should be disclosing the crime or incident reports to the community because it is serving a public function.

“If you have a police force out there that is acting like a police force, even though it is for a private institution, the fact that it is arresting people and charging people would tend to tell me it is serving a public function regardless of who is paying for it. People should have the right to know what is going on with their police force. You don’t want there to be no accountability for people who have to operate under the constitution,” Dyer said.

According to Frank LoMonte, the executive director of the Student Press Law Center, it has not been tested by law yet in the state of Ohio whether or not a police force for a private institution fits the function of a government agency.

The Ohio Revised Code that gives private colleges the authority to have their own police force says that these police forces are supposed to be vested “with the same powers and authority that are vested in a police officer of a municipal corporation or a county sheriff under Title XXIX of the Revised Code and the Rules of Criminal Procedure.”

Despite the records that were not released, a few requested articles were eventually disclosed. Among these were a blank parking ticket, an exact number of parking tickets issued and some parking committee minutes.

According to these released documents, from July 2011 to the end of January 2012, 806 parking citations were issued across campus lots.

Other factors

Some information was not disclosed because the justice system at Otterbein is split into two divisions, criminal and judicial.

If a student is charged criminally, charges appear on that student’s criminal record, which is public.

If, however, a student is investigated through the judicial review process, the charges are not disclosed to the general public.

“Regarding disclosure of personally identifiable information, we follow the guidelines identified by (the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act). According to FERPA, the only time we are allowed to disclose personally identifiable information regarding student records and disciplinary hearings is in the case of a victim of an assault,” Robert Gatti, vice president and dean of Student Affairs, said in an email statement.

LoMonte said, “I suppose you could argue that there is some benefit (of FERPA) to the students who break the law that they are able to avoid creating a paper trail that will haunt them later in their lives, but I am not sure that is really “beneficial” to society. There is a reason that every state has declared that information from police reports is a matter of public record, and to create a double-standard where crimes committed on college campuses are invisible seems to undermine that public policy.”

Dyer said further, “You should be able to walk into any police station in the state of Ohio, ask for the incident reports and get them and go through them and be able to find out what your police force is doing. Otherwise … they are not being held accountable; you need to hold them accountable.”

Otterbein President Kathy Krendl did not respond to multiple interview requests via email and phone by the time this story went to press.

National Scrutiny

Otterbein is not alone in its system. Private colleges with police forces exist all over the country, but recently a couple of states have ruled that those police forces act as agents of their respective states, and not those of the schools of which they patrol.

In the state of Indiana, for instance, Judge Rudy Lozano ruled a little less than a month ago that the University of Notre Dame Police Department was liable for the lawsuit against them by a pro-choice protester on their campus that claimed the police violated her First Amendment rights and falsely arrested her.

The defense of the police department was that only government officials could be accused of violating the Constitution, and they represented the private entity of Notre Dame.

Lozano noted in his opinion and order that the “broad grant of power to police officers for private universities leaves little to differentiate them from any other police officer in the state of Indiana, at least if they are on the university’s property.”

Also, in North Carolina in November 2011, the state Supreme Court ruled that the Davidson College police in North Carolina were ultimately under the power of the state, after a student’s attorney argued that her drunk-driving arrest should be thrown out because Davidson is a church-affiliated college and the state can’t delegate its police powers to a religious institution.

The court said, “When campus police officers exercise the power of arrest, they must ‘apply the standards established by the law of this state and the United States.’”

Otterbein enforcement a one-stop shop

Currently, all the roles and responsibilities of the judicial process at Otterbein — the charges, the judge, the jury, the prosecutor and the best interest of the student — reside in the same department of Student Affairs. This structure, however, is not atypical in the Ohio Athletic Conference. Six other schools in the conference — John Carroll, Marietta, Mount Union, Muskingum, Ohio Northern and Wilmington — are structured with all processes running through Student Affairs.

“This structure seems problematic,” LoMonte said. “From a public disclosure standpoint, it helps the colleges make the case that records created by police are really disciplinary records.”

LoMonte said that this structure has the people who are accusing a student working for those who are prosecuting the student through the disciplinary system.

“In theory, it could also create a ‘conflict of interest’ situation … (but) at some level everyone in the process will work for the university, just like the police and the prosecutor all work collaboratively together for the ‘state’ in the off-campus world, so you can never have a wall of separation there,” LoMonte said.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article was published in the Tan & Cardinal on April 25, 2012.